Cecilio “Pepe” Vega, lead for victim services outreach, is often out in the community, visiting HVIP clients to see how they’re doing and ensure they’re receiving the assistance they need. His victims services outreach position is one aspect that makes YNHH’s program unique.

YNHH program connects hospital and community to help break the cycle of violence

Bullets can be removed, wounds stitched, broken bones reset.

But the team with Yale New Haven Hospital’s Hospital Violence Intervention Program (HVIP) knows that acts of violence have other, far-reaching effects that victims need time and assistance to overcome.

“Many of these patients often have good outcomes with their physical wounds,” said James Dodington, MD, HVIP medical director. “It’s the unseen wounds that have the biggest impact.”

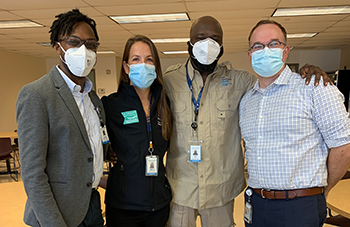

YNHH’s Hospital Violence Intervention Program, the first program of its kind in Connecticut, recently received a federal grant that will help cover current costs and an additional social worker. The current team includes (l-r): Antwan Nedd, LCSW, lead victim services navigator; Marcie Gawel, RN, community outreach coordinator; Cecilio “Pepe” Vega, lead for victim services outreach; and James Dodington, MD, medical director.

Established in 2020, YNHH’s HVIP serves people 18 and older in Greater New Haven who are victims of shootings, physical assault, sexual assault, human trafficking and intimate partner violence. HVIP staff work with hospital and community resources to ensure program clients receive needed medical, mental health, employment, financial, housing and other types of assistance. The program’s goals are to help clients recover and prevent future re-injury.

“We know that violence is a public health crisis,” said Nick Aysseh, HVIP manager. “This program bridges health care and public health to help people get on the right track, and break the cycle of violence.”

YNHH’s HVIP recently received a nearly $400,000 federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grant. Funds will help the program cover current costs, add a social worker and enroll at least 100 clients in the coming fiscal year. In addition to Aysseh and Dr. Dodington, the HVIP team includes Marcie Gawel, RN, community outreach coordinator; Antwan Nedd, LCSW, lead victim services navigator; and Cecilio “Pepe” Vega, lead for victim services outreach.

Here’s how the program works: Dr. Dodington and Gawel identify patients who have experienced certain violent incidents and might benefit from the HVIP. Nedd contacts these patients to see if they want to participate in the voluntary program. If so, he works with people at the hospital and a variety of state and community organizations to arrange for assistance. For example, one client spent several weeks in the hospital as a result of her injuries. The HVIP team worked with local churches and other programs to ensure her rent was paid and she received help with other financial needs.

The HVIP can also arrange assistance for clients’ loved ones. For one client who was assaulted in the presence of her child, the team secured mental health services for the child.

While assistance is customized for each client, victims of certain types of violence tend to share similarities, Nedd said. Many gun violence victims are men ages 18 to 25 who are unemployed, under-educated, lack adequate housing and are experiencing untreated trauma. Many trafficking victims are women ages 18 to 24 who are disconnected from their families and have a history of trauma. Intimate partner violence can affect people of all ages, education levels and socioeconomic status.

One unique aspect of YNHH’s HVIP is Vega’s role. He follows up with clients – by phone or home visit – to see how they’re doing, ensure they’re receiving the care and assistance they need and secure any additional services. A lifelong New Haven resident and former victim of gun violence, Vega is a “credible messenger,” Dr. Dodington said.

“With this population, it is very hard to make connections,” he said. “We need to build trust, and Pepe does that.”

“I’ve lived in this community my whole life,” Vega said. “I’m always out mingling with people, so they know me, and they know I’m there to help.”

He and his HVIP colleagues do help, despite daunting statistics: Nationwide, violent injuries are a leading cause of disability and death among people ages 15 to 34. Nedd recalled a client who had been shot several times and spent three weeks in the hospital. Nedd connected the patient and his family with a clinic providing post-traumatic stress disorder counseling, and Vega helped the young man get a job.

“He is feeling and doing well,” Nedd said. “There are multiple stories like that.”